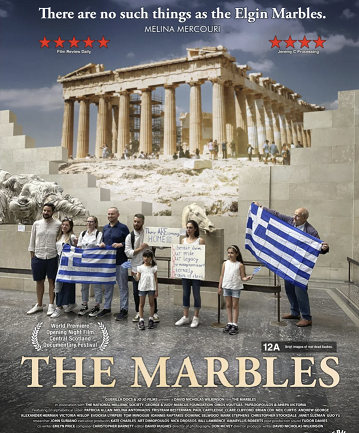

The film The Marbles about the Parthenon Sculptures has been released in British cinemas: Let them go!

- Written by E.Tsiliopoulos

David Wilkinson’s documentary The Marbles has been in UK cinemas since yesterday, with Succession star Brian Cox becoming the loudest voice for the reunification of the Parthenon Marbles.

There are stories that don’t end with rhetorical exclamations but with a quiet, unnegotiable certainty. David Wilkinson’s documentary The Marbles doesn’t raise the tone; it lowers it enough to make clear what has been drowned out by the noise of excuses for two centuries: the Parthenon Marbles must be reunified. And while public debate often gets bogged down in legalistic twists and turns, the director chooses the straight path. Not to punish, but to enlighten.

The film’s starting point is – not coincidentally – March 25, 2021, the two hundredth anniversary of the Greek Revolution. On that day, Wilkinson opens the camera and, in essence, sets a moral timer: from now on, every postponement of return is measured against an anniversary of freedom.

The documentary, which was released in cinemas in the United Kingdom on November 6, begins in the courtyard of the British Museum, among protesters and visitors waiting patiently; a ritual of urban culture with a simple, mouth-watering question asked by the great actress Janet Szasman: “Do you want to know how they got here?” The question functions as a prologue to a collective confession.

The “lone villain”: not a museum, but an earl

The Marbles avoids demonizing. The director himself soberly states that the British Museum is not the “villain” of history, but the method of acquisition. The film approaches Thomas Bruce, seventh Earl of Elgin, not as a historical figure, but as an archetypal figure of European arrogance: the one who translated plunder into a “civilizing mission.”

The famous Ottoman “firman” never appears in its original form; its translations are questionable; the “legal purchase” is more like an acquisition. Wilkinson does not shout, he lets History speak in its own light.

Scotland: a different consciousness of return

It is no coincidence that the world premiere took place in Scotland. The choice functions as a statement: a country that has set examples of returning cultural goods becomes a stage for calmly but decisively articulating the need to reunite the Marbles. The film uses the Scottish experience as a moral mirror to English institutional conservatism, not to fuel an internal British rivalry, but to show how restoration can be done with order, respect and institutional purity.

At the center of the work is a sharp phrase: “It’s time to just say: let them go.” Brian Cox, the iconic Scottish actor who became world-famous for the wonderful TV series Succession, speaks without pomp, with the severity of the obvious: “The Marbles are the Parthenon, as simple as that.”

This is not a philhellene romanticism, but a publicly maturing Anglophone consciousness: the sculptures were removed when Greece was under Ottoman occupation, therefore at a “false moment” for any agreement. His statement functions as the axis of the narrative; a moral compass that points steadily towards reunification.

“Global” occupation or global consciousness?

The Marbles coolly reconstructs even the arguments in favor of staying in London: “better conservation,” “global access,” the idea of the great museums as “neutral zones” of culture. Wilkinson introduces two cracks in this picture:

The reality of custody. The recent cases of thefts from the British Museum’s storage facilities strike at the heart of the myth of foolproof security. This is not a charge, but an observation: no institution is above risks and inertia.

Digital consolation. Technology promises VR representations and “meta-museums”. The film, without technophobia, underlines the obvious: the digital cannot replace place. Art is not only form and dimension; it is also climate, light, temperature. It is the breath of the space that gave birth to it.

The “small” returns that prepare the big

The narrative runs through the silent, essential movements of recent years: fragments returning from German and Italian collections, simple but weighty ceremonies of delivery. Wilkinson’s lens does not dramatize. It rests on hands that deliver and receive, on the natural light that changes texture on the marble when it emerges from the English patina. There you understand that it is not a matter of "national property", but of the essence of place: matter meets the light that nurtured it.

One of the greatest strengths of the film is that it does not approach its subject with a charge, especially towards the people of the British Museum. The director recognizes their generosity, availability, care and does so from the first

hand. During the filming, he himself was battling terminal cancer. The image of him walking through the halls, weakened by chemotherapy, without a trace of melodrama, functions as an anti-manifesto: the message is not “burn the museums” but “unlock their consciences”. The museum, after all, is its people and their ability to look history in the face.

Political maturity and cultural adulthood

The issue of the Sculptures is not a Greek demand but a European test of sensitivity. The postcolonial debate around museums is not just about who owns the works, but who defines memory. Wilkinson, with a sobriety that does not dry up emotion, argues that the return will not be an act of nationalism, but an act of cultural adulthood. Europe will be judged not by its ability to preserve, but by its ability to repair.

In the scenes of Athens, light writes with its own spelling. The Parthenon is not projected as a postcard, but as a rhythm that persists in the chaos of the city. The viewer literally sees what contextual means: how a frieze “sounds” differently when, behind it, the monument itself stands; how marble breathes when it finds its climate. It is the most powerful, non-verbal counterpoint to any proposal of “digital substitution”.

The private becomes universal

The Marbles is also a work of personal endurance. Wilkinson speaks openly about his illness, about how work became therapy in the darkest period. He does not instrumentalize the experience; he documents it to explain the tone of the film: not resentment, but restoration. When, in one shot, he emerges from the British Museum and “disappears” into the light of day, the viewer does not see a triumphant man, but a man who has completed his duty.

The Marbles sets the record straight without lifting a finger. When it talks about Elgin, it does so with the sobriety of the lens. When it gives space to the defenders of the stay, it does not ridicule them. That way it remains credible.

“This will only happen under a Labour government,” the director says in an interview, answering the question about the conditions for the return of the Sculptures to Greece. “If Nigel Farage is elected, then there is no way it will happen. I think that, at the end of the day, the English establishment – I won’t even call it British – doesn’t like to be seen as intimidating. And yet, in our history, we have been the bullies many times. But we don’t like to seem to be doing the wrong thing, all this cricket rhetoric about “playing fair”. When you see other countries, like the Netherlands, taking the initiative on the issue, and I would put Scotland even further ahead, then the embarrassment sets in and the question becomes: do you want to be the last one standing?”

In the end, there is a clear proposition to all politicians, curators, citizens: if museums are “universal”, universality is judged by their ability to correct History, not to prolong it. If Europe really wants to face its past with honesty, the reunification of the Parthenon Sculptures is the right starting point. Not because they “belong to Greece”, but because here – and only here – they find a voice again.

Or, as Brian Cox sums it up, without philosophical paraphernalia: "Let them go."

Media

Related items

-

Israeli protection for Greek skies

Israeli protection for Greek skies

-

Fierce attack on kickboxer Giannis Tsoukalas in Serbia after winning the WKU professional world title at -67 kg by knockout

Fierce attack on kickboxer Giannis Tsoukalas in Serbia after winning the WKU professional world title at -67 kg by knockout

-

St. Nicholas Greek Orthodox Church: A final Stewardship appeal before year’s end

St. Nicholas Greek Orthodox Church: A final Stewardship appeal before year’s end

-

Greek hoteliers gift 50 families free all-inclusive island vacations to start 2026

Greek hoteliers gift 50 families free all-inclusive island vacations to start 2026

-

New traffic code and breathalyzer tests caused a plunge in consumption in nightclubs

New traffic code and breathalyzer tests caused a plunge in consumption in nightclubs

Latest from E.Tsiliopoulos

- Israeli protection for Greek skies

- Fierce attack on kickboxer Giannis Tsoukalas in Serbia after winning the WKU professional world title at -67 kg by knockout

- St. Nicholas Greek Orthodox Church: A final Stewardship appeal before year’s end

- Greek hoteliers gift 50 families free all-inclusive island vacations to start 2026

- New traffic code and breathalyzer tests caused a plunge in consumption in nightclubs