The hidden threats behind Turkey’s UNESCO map – The “Blue Homeland”, the disputed maritime border and the grey zones

- Written by E.Tsiliopoulos

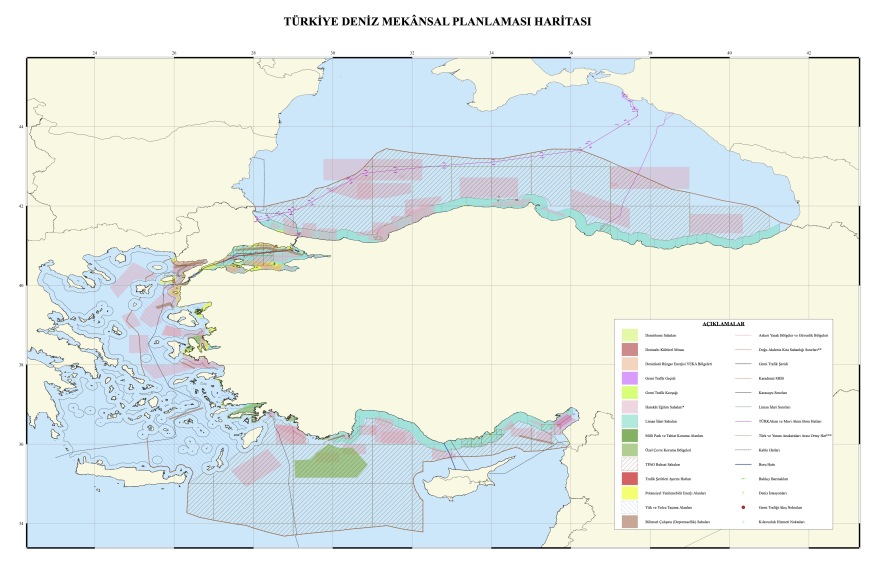

Turkey is attempting to legitimize its “Blue Homeland” at an international level and with the “glamour” of UNESCO by Turkey with the submission of the well-known Marine Spatial Planning Map, which had first appeared on April 16 and depicts all of Turkey’s claims against our country.

Turkey had previously announced the submission of the Marine Spatial Plan (MSP) to UNESCO and this move seems to have been accelerated in response to the Greek MSP, but also to the announcement of the creation of a Marine Park in the southern Cyclades by Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis last week in Nice at the World Ocean Summit.

See the map:

Turkey submitted the map elaborated by the Turkish DEHUCAM Institute to the platform maintained by UNESCO and the Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission (UNESCO-IOC), in fact in cooperation with the Commission (Directorate-General for Maritime Affairs and Fisheries – DG MARE) for the development and implementation of the guidelines for Marine Spatial Planning.

Turkey chose to submit the map to this platform, even though the relevant page for the Republic of Turkey highlights that the map comes from the scientific and governmental institute DEHUCAM, with the notation, as is the case for all TCM maps, that: “The areas on the Marine Spatial Planning map indicate project implementation zones and do not necessarily imply state jurisdiction” . However, it is pointed out that the competent authority in Turkey for the Marine Spatial Plan is the Presidency of the Republic of Turkey,and therefore this map has a more official form.

The reaction of the Greek Foreign Ministry was strong, which in yesterday’s statement noted the following:

“Turkey today published a maritime spatial planning in response to the Greek planning, which is already part of the European acquis. The difference is that the Turkish map has no basis in international law, as it attempts to usurp areas of Greek jurisdiction, and is not addressed to an international organization that imposes an obligation to post relevant maps. Therefore, it does not produce any legal effect and is simply a reflexive reaction of no substance. Greece will insist on its principled policy and calls on Turkey not to make maximalist claims that everyone understands are for internal use only. Greece will take appropriate action in all international forums.”

The text accompanying Turkey’s submission to the UNESCO platform (and coming from the Turkish Maritime Spatial Planning Platform) admits that the Turkish EEZ has been declared only in the Black Sea through agreements with other coastal states. It argues that there are legal delimitation agreements with Libya and the “TRNC”, and that delimitation remains pending with Greece, where, until then the unilateral declaration of the outer limits of the Turkish EEZ at the UN in 2020 is in force.

Invoking the 1976 decision of the International Court of Justice that “the areas of the continental shelf (in the Aegean Sea)… are considered by the Court, a priori, as areas under dispute, and for which Turkey also claims rights of exploration and exploitation”, Turkey states that the boundaries in the Maritime Spatial Planning Charter concerning maritime jurisdictional zones beyond the (Turkish) territorial waters in the Aegean Sea represent the median line between the continental parts of Turkey and Greece, until a delimitation agreement is concluded between the two countries," Turkey also states.

Also, as far as Syria is concerned, the Turkish side states that the same map applies, but the “maritime oblique delimitation between Turkey and Syria remains to be delimited”. This is related to the difference between the two countries regarding Alexandretta, but also to the demarcation attempt through a Turkish-Syrian Memorandum at the expense of the Republic of Cyprus.

In the Aegean, the Turkish side says that no agreement has been reached with Greece and again invokes the Bern Agreement (1976), which it describes as a “binding document” that provides for the commitment of the two countries to refrain from any action or initiative that could disrupt negotiations to resolve the dispute over demarcation, which is an interconnected issue in the Aegean.

However, Ankara insists that there are no maritime borders between the two countries, arguing that they have not been fully demarcated and “therefore, the boundaries of the territorial waters between the two countries are not depicted,” while presenting the Turkish position on the need for “fair resolution of disputes over maritime boundaries based on the principles of equality as defined in relevant international jurisprudence.”

Ankara also disputes the existence of a “lateral border with Greece” regarding the projection of the Evros estuary.

Finally, there is a special reference to “grey zones” in this text as well and it is stated that “There are numerous small islands, islets and rocky islets in the Aegean Sea, the ownership of which was not ceded to Greece through international treaties. Most of these geographical features cannot sustain human habitation and have no autonomous economic life. In maritime zones where such features exist, maritime boundaries reflect only the territorial waters of the mainland and do not necessarily reflect sovereignty boundaries. Such boundaries on the map cannot be construed as recognition or acceptance of any claim to jurisdiction.”

However, the contradiction in the Turkish platform, which is now being promoted by the MSPglobal (UNESCO Commission) platform, is the admission that Turkey has not yet adopted Marine Spatial Planning, although numerous studies have been carried out in the country. Furthermore, no national legislation on the MPA has been adopted, although reference is made to laws that have been adopted in a piecemeal manner, the latest being the “Action Plan for Sustainable Blue Economy – Blue Plan” (2025); however, likely, it will soon be adopted as national legislation.